The Anatomy Gallery

Planes of Movement 101

Skeleton in the (jam-packed) closet. Here's a quickie planes of movement lesson.

Establishing a language we can use to describe movement is a fundamental component of any anatomy course. Using amusing demos (and finding opportunities to dance around—watch to end) are fundamental to making learning fun.

The abdominal obliques rotate your spine.

What does gluteus medius do?

What does gluteus medius do? Abducts your hip (moves your leg away from the midline), right? Right. But that’s not all.

The fibers of gluteus medius run in three different directions. These varied lines of pull enable glute med to create a couple other movements as well, as I illustrate in this video. (Not shown here: the anterior fibers also internally rotate the hip; the posterior fibers assist in external rotation.)

PS: Gluteus minimus works the exact same way. It’s smaller than and deep to (meaning underneath) glute med, but its fibers are oriented the same way and so it creates a variety of hip movements. I point this out because I sometimes hear gluteus minimus hailed as the muscle that internally rotates your hip. Only its anterior fibers do that. And they’re just helpers: gluteus medius and TFL—plus a bunch of your inner thigh muscles—team up to turn your thigh in. As is so often the case with the human body, it’s a group effort!

Is tilting the pelvis in warrior 2 a "misalignment"?

The quote marks should foreshadow my answer. Sometimes the pelvis tilts in warrior 2 because the practitioner isn’t aware that it’s happening. In that case, working on leveling the pelvis can improve coordination and proprioception (the awareness of the body’s position in space). Other times, the back hip NEEDS to lift. Here are a couple reasons why:

Bone structure. You know how we all have different personality traits? Well, our bones have unique shapes too. Femoral necks take different angles. Compare the spaces indicated by the purple dots. See how there’s less distance between the green and red lines in the top photo? Imagine a femoral neck/shaft that angles outward. That space would be further decreased, potentially causing owie pinching. See how tilting the pelvis in the bottom image increases the space?

Tight inner thigh muscles. If the inner thigh muscles, the adductors, of the BACK leg resist stretch they’ll cut themselves some slack by tipping the pelvis forward. Compare the angles marked by the orange dots. See how the bottom shape requires less stretch? The green and red lines are closer together there.

Sometimes a “misalignment” is just the right alignment for an individual body.

Where are your floating ribs?

Do you know where your floating ribs are? I often hear yoga teachers use this term in reference to the lower front ribs. Your floating ribs are, in fact, in the back. Watch this video to locate your floating ribs on the skeleton and then to palpate them on your own body.*

*One important caveat: I have really, really long 11th ribs. So you’ll see my fingers discover their floating ends way out on the sides of my torso. If you find yours more toward the back, you’ve landed on the spot we’re seeking.

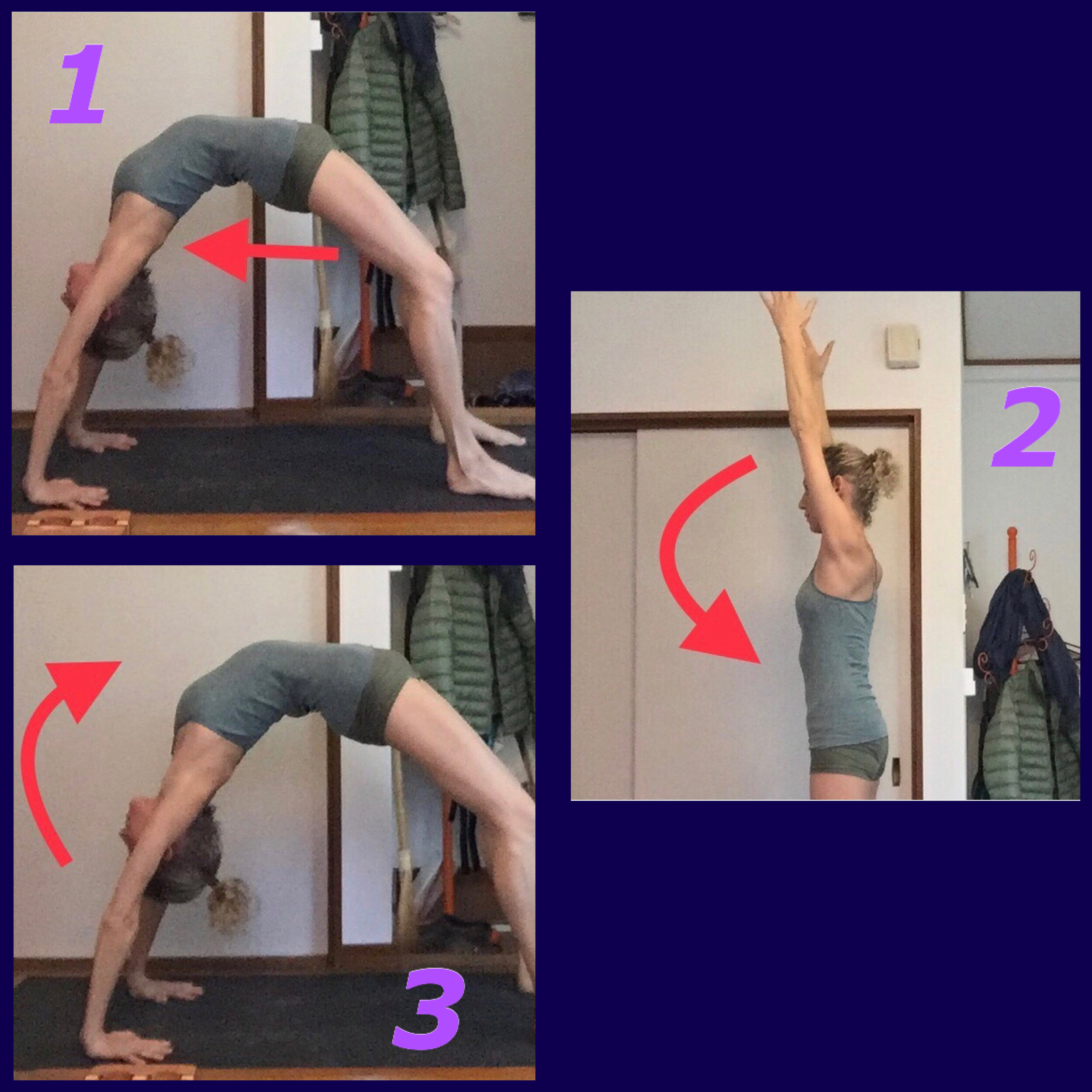

Wrist compression in urdhva dhanurasana?

“My wrists hurt in urdhva dhanurasana. I must have weak wrists.” Maybe it’s a wrist issue. Maybe it’s because restriction in the shoulders is demanding extreme wrist extension.

Imagine if I were able to shift my shoulders directly above my wrists in photo no. 1: the wrist angle would be much less acute.

I can’t move my chest in that direction because it’s challenging for me to flex my shoulder to the degree required here. When I raise my arm in photo no. 2, tension in my tissues pulls my arm forward of my ear, or down toward my chest.

Flip that situation upside down (photo no. 3). If I can’t eke out the shoulder mobility this pose asks, I’ll find the range of motion elsewhere, in this case in my wrists.

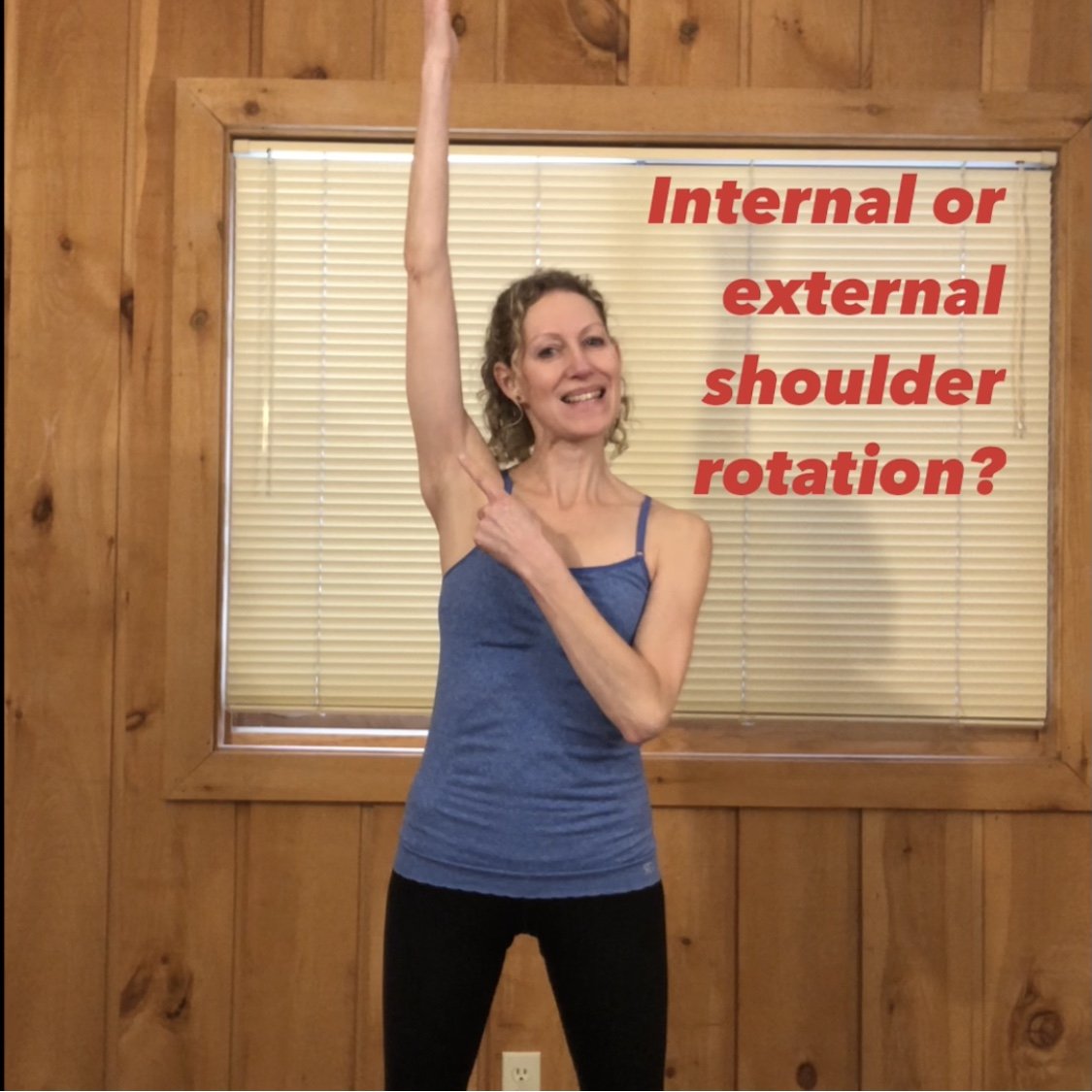

Internal or external shoulder rotation?

When your arm is overhead, is your shoulder internally or externally rotated?

Lots of yoga poses raise the arms above the head. Cueing the shoulders in this position can be tricky. While it feels like the arms are spinning “in” (toward your face), the anatomical position of the shoulder joint is external rotation. Watch this video for a quick demo.

Then consider: Should we cue “roll your arms in” in down dog? How do we cue the shoulders in a way that’s comprehensible to students and still anatomically accurate? Should we privilege clear communication or anatomical veracity?

I tend to weight both equally. That means I need to find cues that make sense to people but that also precisely describe what the body’s actually doing. What are your go-to cues when you need to say something about shoulder rotation? (To be clear: sometimes we needn’t say anything!)

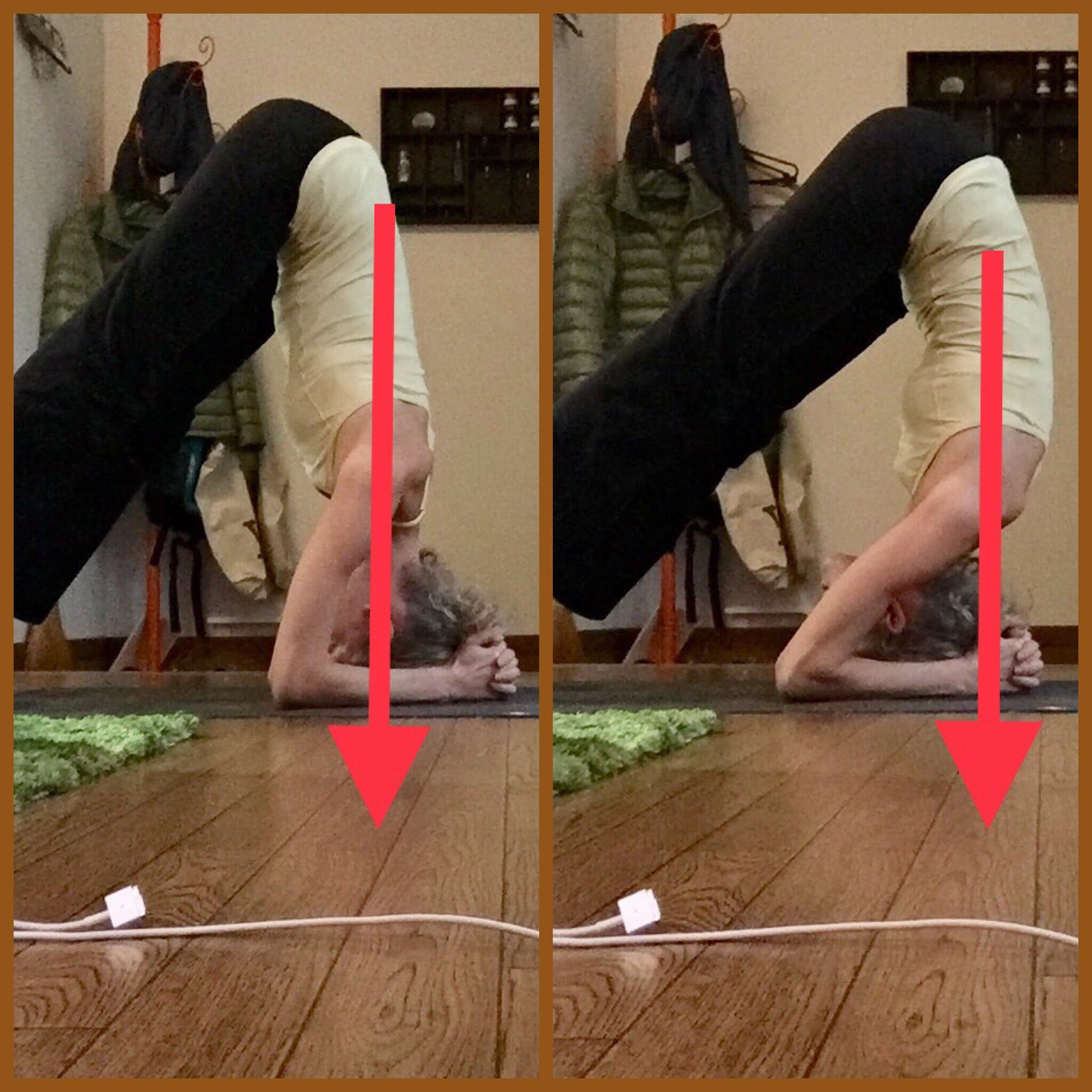

Arm length in headstand: body proportions matter!

Body proportions affect asana practice. Here’s an example. Observe me and Japanese translator extraordinaire Aya Itakura in headstand position. My arms are so long, my head doesn’t reach the green line. When I practice sirsasana, I need a narrowly folded blanket under my head to make up the difference. In Aya’s case, her arms don’t reach the green line. She’s basically doing niralamba sirsasana (headstand without the support of the arms). In practicing this inversion, she benefits from a folded mat tucked under her elbows so that she can ground them down. We each adapt the template to our personal forms.

Placement of back foot in warrior 1

When you go to the shoe store, you find a pair of kicks that fit you, right? You don’t cram your dogs into a shoe that’s not your size or style. Try on your warrior 1 the same way. Compare these two iterations. Note the angle of the back foot, the length of the stance, the pitch of the front thigh. I’m the bottom photo. I’ve got a fairly long stance and a deep bend in my front knee. In order to descend my front thigh so much, I need to turn my back toes out a good bit. In the top photo you see Yoko Tokumoto opting for a much shorter stance. That permits her to wrap her back hip farther forward than my variation allows. Her back toes are also turned much farther forward than mine are. I don’t have sufficient ankle dorsiflexion to turn my toes so far forward, even with a shorter stance. When Yoko turns her toes to the side, she feels discomfort in her knee. We’ve each selected footwear that suits our personal tastes.

Weight-bearing on the hands in down dog

“Press the base of the index and thumb to protect your wrists in down dog.” Sound familiar? Why does rooting that side of the hand sometimes relieve or stave off wrist discomfort? I’ve created this 2-minute video tutorial to explain the anatomy behind the cue. The Y behind the Q.

Long arms: body proportions matter!

You’ll note that I can’t manage a straight line between my upper arms and my trunk. I have (relatively) limited shoulder flexion available. That’s one of the reasons I prefer this block variation: without it, my hands drift toward the midline. Slipping the palms toward center (internal shoulder rotation) is one way to reduce resistance in shoulder flexion. Many who share my challenges in this range find that their forehead knocks against the block. As you can see, I have sufficient clearance. So how do I pull off this inversion despite restriction in range of motion? I HAVE REALLY LONG ARMS. Imagine if my arms were a couple inches shorter: I’d headbutt the block. Body proportions do play a role in what shapes are available or challenging for us.

Elbow lift addresses shoulder resistance in forearm stand

What differences can you spot in these two iterations of pincha mayurasana? My shoulders are (relatively) restricted in this overhead position. The blanket lift under my elbows helps create a bit more space. Notice that my back is slightly more arched in the left-hand photo. Since I can’t find any more shoulder flexion, I’ve backbended my spine. The elbow lift on the right feels less effortful (not a visible difference, of course). On the other hand, the squishy blanket and interrupted contact between forearms and the floor sometimes registers as less stable for students. You gain something and you lose something with every variation…

How Muscles Move Bones

How do your muscles move your body? They pull one bone toward another. They can't push. Watch this door illustration to learn how your muscles move you around.

Outer knee pain in backbends?

Do you get pain in your outer knee in backbends like this one? Here’s one possible reason: Your IT band (goldish tape) is a strap of fascia that runs down your outer leg and attaches below the knee joint. Your gluteus maximus (red tape) attaches to it. In this backbend gluteus maximus works to lift your hips away from the floor. Its contraction also turns your legs out. Your teacher tells you not to let the legs turn out. So you engage the muscles that roll them back in. One of these muscles, tensor fasciae latae (blue tape), also attaches to the IT band. TFL and glute max are essentially playing tug of war with the IT band, which puts the IT band under tension. This tension sometimes pulls the IT band’s attachment on your lower leg toward your thigh. The result is a pinching sensation on your outer knee. Solution: widen your feet to give the IT band some slack.

NB: The tape shows the location of these structures and the direction in which their fibers run. It does not demonstrate their breadth. Your IT band is wider than the tape and glute max is HUGE.

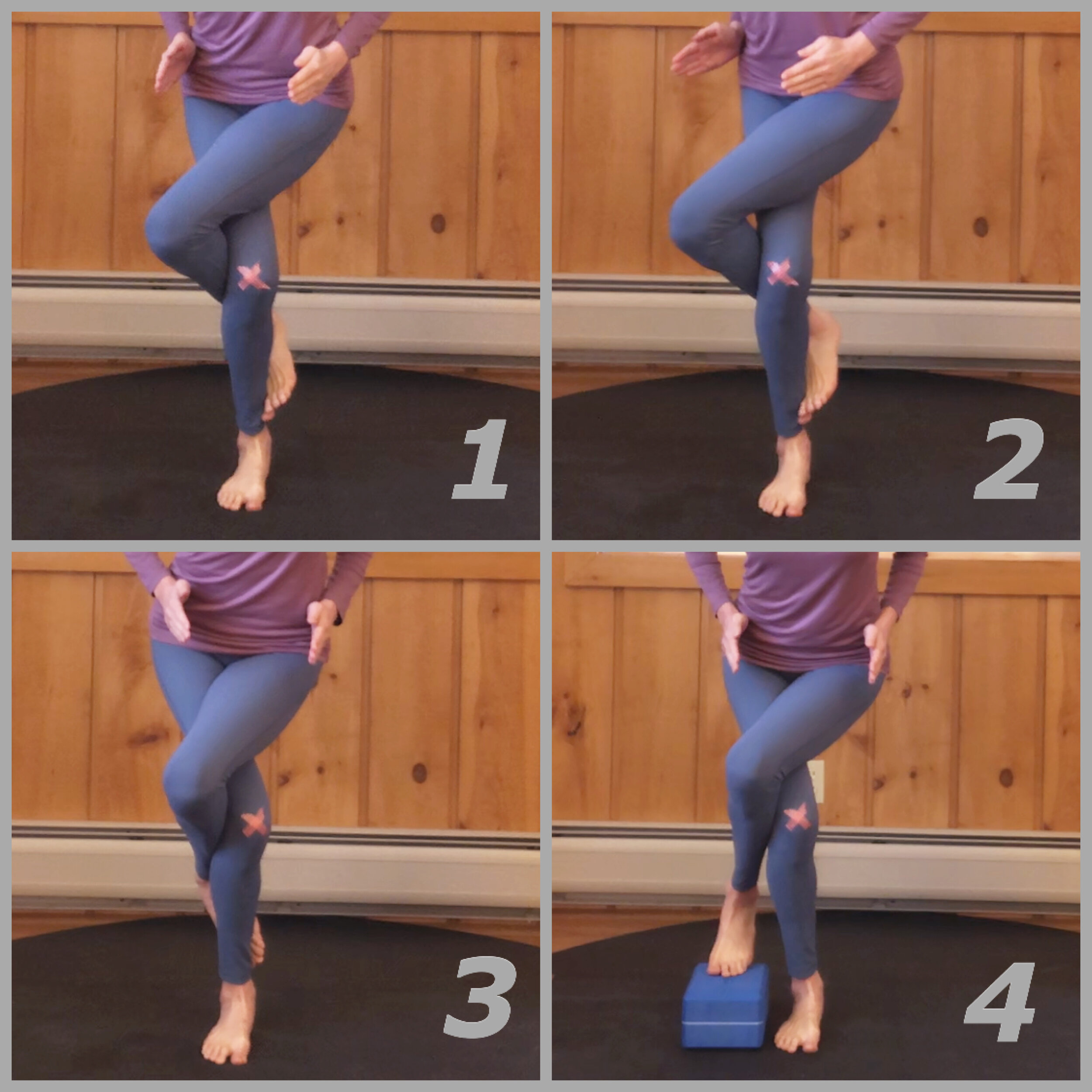

Where should you align your knees and hips in eagle pose?

Four eaglets in a nest. Where should you align your knees and hips in garudasana?

1️⃣ This is your standard eagle pose. Note that my hips are facing on a diagonal. My standing knee (❌ marks the spot) is rolled in slightly. Gasp! Mustn’t the knee ALWAYS align with the second and third toes?

2️⃣ Look how far I have to turn my hips and torso to align my knee ever the middle of my foot. In fact, a bent knee does allow some rotation and in photo 1 I’m well within the average 30 degrees available in this position. (Not that I measured with a goniometer.)

3️⃣ By contrast, when I try to square my hips to the camera, my knee rolls way in. You can’t see this, but I’m also dropping the inner arch of my standing foot. My foot bones are helping to eke out a bit more space as I attempt to turn my pelvis forward. I’m also tilting my pelvis laterally in attempt to bring my aerial hip back. That further challenges the hip muscles tasked with stabilizing my standing leg.

4️⃣ I love this variation. My knee still rolls in slightly, but there’s less pressure on it, since I haven’t wrapped my lower leg. And needless to say the block adds tremendous stability.

Why a bolster alleviates back discomfort in savasana

Does your lower back get cranky in savasana? Does propping your knees on a bolster alleviate the ache? Why does support under the knees often relieve back discomfort in savasana?

Here’s one of many possible answers. When you lie flat, your psoas is pulled taut. Note that when I pluck the band in this position, it doesn’t allow much give. The psoas attaches to your lumbar (lower) spine. If it’s tensioned in savasana, it may tug on your lower back, causing general owieness. When I bend my knee, the band goes slack. That release of tension can afford my back greater ease.

Aligning the pelvis and knee in tree pose

Where should your hips and bent knee face in tree pose? When it's straight, your knee doesn't permit rotation. So the standing knee takes priority and the pelvis lands where it lands. Watch this short video for a primer.

The knee is a weird joint.

Here’s one of many asana implications to be extrapolated from the lesson contained in this video snippet: When it’s bent, your knee allows some rotation. That means that, if the front knee rolls in a little in warrior 2, the sky won’t fall. Average range of motion available there is about 30 degrees. So if you’re within that pie slice, you’ll probably be just fine.

Should yoga teachers still cue aligning the knee over the second and third toes? Sure. No need to throw out the baby with the bath water. Stacking the knee over the ankle in this way ensures that students don’t over-rotate the knee in this weight-bearing position. Perhaps more important, attending to this detail teaches awareness of where the body is in space. That ability to self-sense may go further than any particular alignment cue in fending off injury.

Is "big toes together, heels slightly apart" a universal cue?

In the photo on the left, I’ve followed the common tadasana instruction to join my big toes and separate my heels. Take a look at my right knee. See how it turns in? Because of the curvature of my lower leg, joining my heels (right photo) allows my knees to track over the centers of my feet. (Actually my right knee is still rolled in a little. My right foot needs to turn out a bit more for my hips to be truly neutral here. But close enough for a brief hold in mountain pose during an asana class!) If you have bunyans, my tadasana foot position won’t work for you because you’ll have to turn your legs out (external hip rotation) to connect your heels. All asana cues serve somebody. Very few serve universally.

Why do we elongate before we twist?

Take a look at the twist in the cutout photo. Note that my right shoulder is much farther forward than my right waist. The upper spine twists a lot more than the lower spine. Why? See the two blue lines on the skeleton? They indicate the orientation of the facet joints—the spot where one vertebra articulates with its neighbor. The facets in the lower spine are oriented more vertically, so the bones abut each other and limit rotation. The facets in the upper spine follow a more horizontal angle, so they can glide farther when you twist. This arrangement affords useful lumbar stability, while permitting the upper body mobility we need to interact with our surroundings.

The juncture between your twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12) and your first lumbar (L1) resembles lumbar facet orientations more than thoracic. So the first place you have real twistability is T11-T12. Notably, the disc between T11 and T12 is a common injury site when people twist, round, and lift heavy objects. Hence your yoga teacher’s warnings against rounding in twists.

BUT... We gotta ask: Can you really exert enough force to injure a disc in a yoga pose? I don’t know. How aggressively are you cranking yourself in there? Is there a pre-existing condition? While your body is sufficiently robust to handle the relatively low load of a yoga asana, elongating before you rotate can’t hurt. (And note that some poses absolutely require you to round and twist. Parsva bakasana anyone?)

Intervertebral discs move when you move.

Blueberry-juice-filled steam cakes—the world’s best edible intervertebral disc. In America I use a jelly donut; students play with mini an pan (red bean buns) in Japan; in Vietnam we make do with macaroons (French colonial influence). These confections from my local Beijing supermarket take the proverbial cake. (I couldn’t resist.) They spring back when compressed, as do your intervertebral discs. And you can actually feel the blueberry filling squishing around inside as you manipulate the pastry, which gives a tangible sense of how the nucleus moves inside the cartilaginous (doughy) portion of the disc. Some students even accidentally herniated their treats by applying too much sudden pressure. Sometimes the learning process gets messy…

How to organize the ankles in up dog

Placing a block between the feet in up dog teaches the actions required to prevent the ankles from sickling (shown bottom left). Bowing the ankles in this pose places stress on the calcaneofibular ligament (pictured in green tape bottom right). If you then roll to down dog with your ankles in this position, that ligament (the most commonly sprained in the human body, by the way) bears still more strain. Use the block to activate the peroneals, the muscles that firm your outer ankles toward the midline. Then re-create that action without kinesthetic feedback from the prop.

Why do you externally rotate your shoulders in down dog?

Externally rotating the shoulders in down dog moves the greater tubercle out of the acromion process’s way and prevents pinching the supraspinatus tendon between the two bony prominences.

The pink tape on the skeleton marks the greater tubercle. The top left shot shows its location in anatomical position or tadasana. In the bottom left corner you can see what happens if the shoulder doesn’t externally rotate when you take the arm overhead—the pink tape bumps into the bony ledge above it. The picture on the right shows the arm in flexion and external rotation. Here, the greater tubercle passes away from the acromion and there’s plenty of space for the soft tissue between them.

Why I don't cue shoulders away from ears in down dog

“Move your shoulders away from your ears” is a useful down dog cue for the person who’s shrugged their shoulders way up by their ears. When given as a universal cue, however, students interpret it as “Depress your scapulae,” and they glide their shoulder blades as far toward the waist as possible. In fact, when you raise your arm overhead, your scapula organically shifts upward a bit toward your ear. That movement lifts the acromion process, marked with pink tape, off of the tendon of the supraspinatus muscle (green tape). If you yank your shoulders toward your waist, you risk pinching the supraspinatus tendon between the acromion process and your upper arm bone.

Up dog variation for a tight chest

This variation works wonders when a limitation in thoracic extension, like restriction across the front of the chest, pulls the shoulders forward. Elevating the hands creates a more gradual spinal extension, so less backbending is required.

Note that the red pipe cleaner is more sharply arced than the green one. The red pipe cleaner illustrates the backbendability required to do up dog with the hands on the floor. The orange pipe cleaner shows that an inability to create such a deep curve will pull the top of the curve (shoulders and chest) forward. The top end of the green pipe cleaner is elevated, resulting in a more gentle arc and enabling more verticality in the upper portion of the cleaner. In up dog, that translates to a less deep, more accessible backbend and a thorax and shoulders positioned above the wrists.

Plow and shoulder stand in the age of Zoom

I’m a big fan of blankets in shoulder stand and plow. To do these poses with the torso vertical requires 90 degrees of cervical flexion. See photo no. 2: my arms and trunk make a 90 degree angle. I’ve bowed my head as far forward as I can. If I had 90 degrees of movement available there, my ears would be in line with my arms. As you can see, I’m nowhere near. Using blankets makes up the difference and I’m able to bring my torso nearly perpendicular to the floor and walk my hands closer to my shoulder blades (photo no. 3). In a Zoom context, where many folks don’t have yoga blankets floating around, I’ve been teaching the plow variation pictured in photo no. 1: my trunk is slanted to keep my neck within the available range and my hands support my lower back. I haven’t been teaching full shoulder stand, since perching the pelvis on the hands puts a lot of pressure on the wrists at an awkward angle. Photo no. 4 proposes a shoulder stand alternative: the block sets my trunk at a much gentler slope than classic shoulder stand, requiring a lesser degree of cervical flexion.

Body proportions matter!

It requires so much effort for me to execute the instructions to lift my chest and draw my arms back by my ears in utkatasana. I feel stuck. Why? Body proportions. I have long thighs and a short trunk. This means that, when I sit back, the weight of my pelvis falls way behind my base of support. So I lean my torso forward and move my arms forward to counterbalance. Then there’s the common instruction to drop weight into the heels, which shifts my hips even farther back. I note that, in this photo, my knees are scandalously far forward. I have a decent amount of ankle dorsiflexion, so I can access the ankle mobility required to shift the knees forward. This shot is actually a still of a video, so I was moving through the pose here and not holding and refining. I’m sure my knees glided forward to bring my pelvis weight forward and make my life easier. (Proof of how much I detest utkatasana? I spent considerable time digging through old photos and capturing a still of this clip just to spare myself having to do the pose for the three seconds required to snap a picture.)

Low back pain in urdhva dhanurasana?

Elevating feet on blocks reduces the hip flexor stretch in this pose. Here I’ve placed my right foot on a block and my left on the floor. Notice that greater hip extension is required of my left thigh. I’ve drawn the lines to improve visibility. (Don’t take them as exact representations of the vectors involved here: I drew on my phone with my index finger.)

Tension in the hip flexors will challenge hip extension in urdhva dhanurasana. As a result, you may find you backbend more in your lower back. If you’re among those who experience lower back discomfort here, try this variation and see if it helps.

Stretch your hip flexors to prep backbends.

Sequencing tip for backbends: include a hip flexor stretch where the knee is deeply bent and one where the knee is straight or almost straight.

Some of the hip flexors, like rectus femoris (one of your quads), cross both the hip and the knee. So to stretch rec fem, you have to tension it across both those joints. You have to bend the knee and extend the hip, as you do in supine hero’s pose. Other hip flexors, like psoas and iliacus, cross only the hip. To target them, take rectus femoris off the stretch by straightening your knee, à la vira 1.

The psoas: stretch is stress.

Stretch is stress. This passive psoas stretch is the most effective way I’ve learned to stretch the psoas. Here’s why it works so well: When you stretch a muscle, you put it under tension, or stress. In response, the muscle fibers contract to resist the stretch. The psoas is particularly responsive to stress. When you’re faced with a threat, your nervous system enters fight or flight mode. Whether you opt to fight (kick) or flee (pump your legs), you need your psoas to spring into action. In the passive hip flexor stretch pictured here, your nervous system gets the message that it’s OK to relax and the psoas can let go.

The set up for this stretch is clear from the photo. What you can’t see is that I’m also doing uddiyana bandha. Uddiyana bandha stretches the diaphragm, which is contiguous with the psoas, so the bandha increases the tug on the psoas. The stretch I feel here is surprisingly dull and deep. It’s not the strong surface stretch I get in an active hip flexor stretch like warrior 1. Try it and tune in.

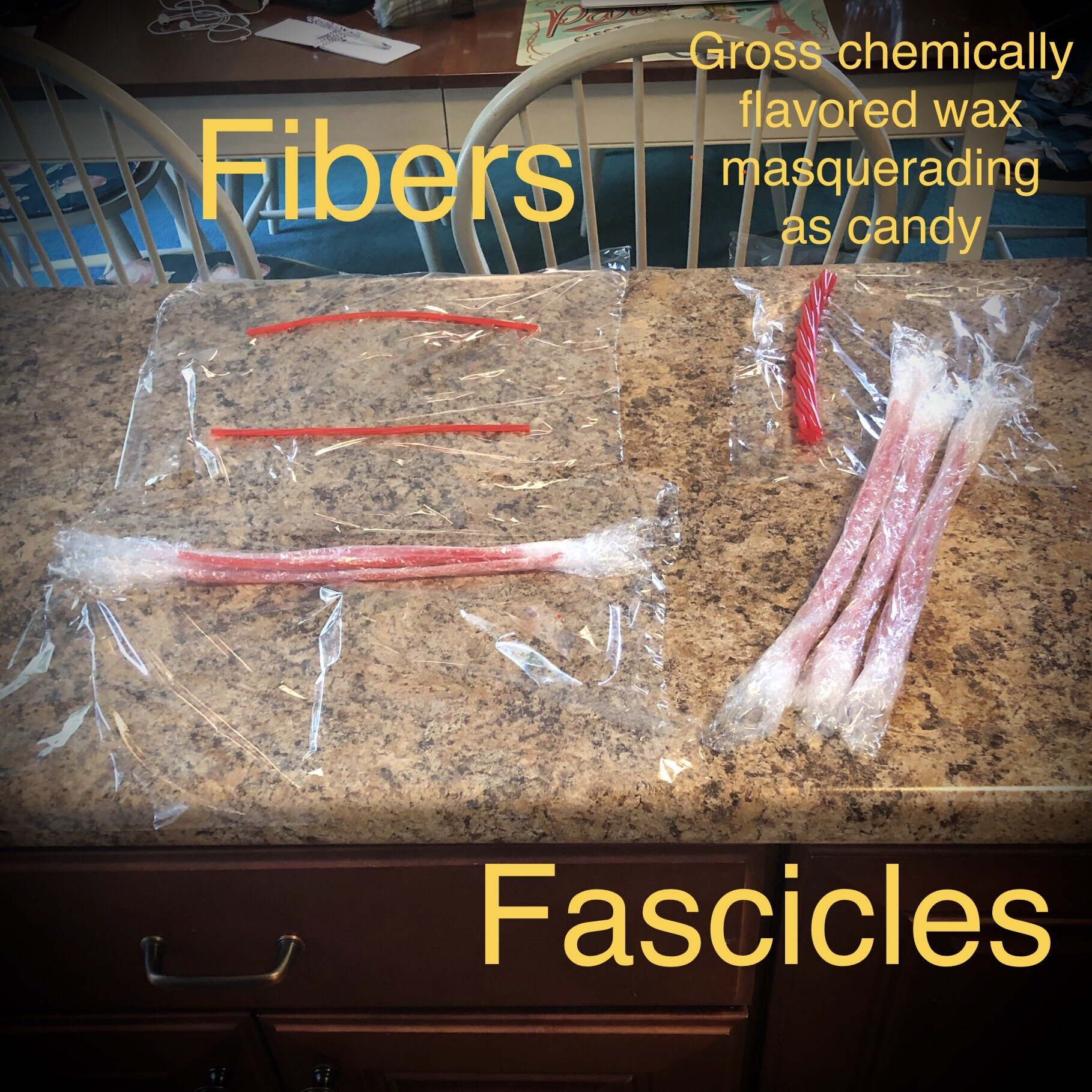

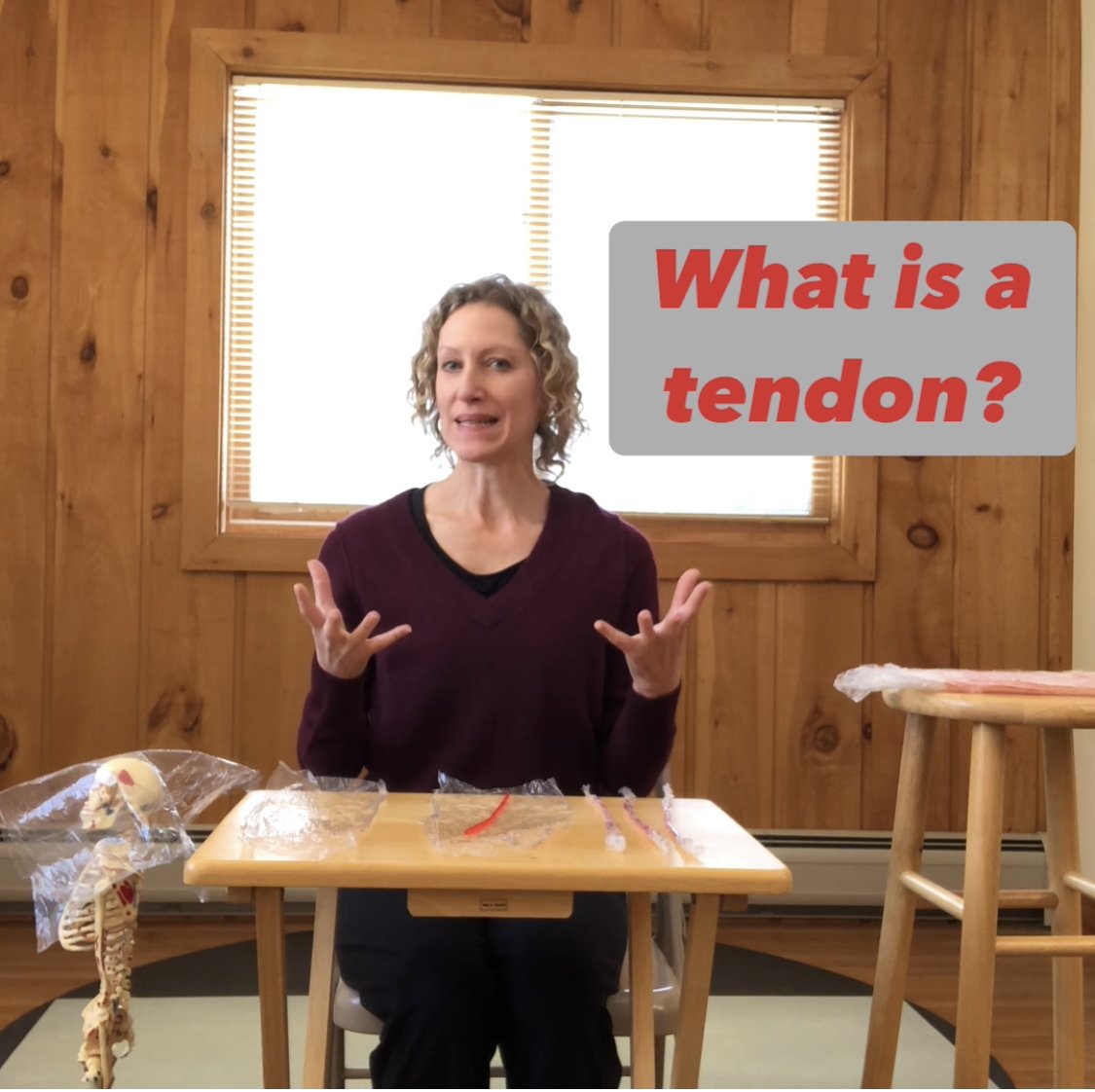

What exactly is a muscle made of?

And what the heck is this fascia stuff we keep hearing about? Muscles are made of individual fibers, conveniently represented in this demo by Pull ‘n’ Peel Twizzlers. Those fibers are wrapped in fascia, mimicked here by sheets of plastic wrap. Bunches of individually sheathed fibers are then grouped together and wrapped in another layer of fascia to form fascicles. The fascicles are then swaddled together in yet another band of fascia to make a muscle (not pictured here). Note I’ve not tucked in the ends of the plastic wrap: the fascia interdigitates and extends beyond the muscle fibers, where it gets labeled “tendon” and attaches the muscle to bone. (Or, more accurately, to yet more fascia encasing the bone.)

Scapulohumeral Rhythm

Say “wings” when you see my shoulder blades start to move.

You can’t move your arm more than about 30 degrees in any direction before your shoulder blades have to move too. Coordinating scapular (shoulder blade) movement with humeral (upper arm) movement is essential for organizing the shoulder girdle in weight-bearing poses like down dog. Note that, as my arms come overhead, my shoulder blades glide away from each other and (...yes...) toward my head. If you’re sliding your shoulder blades toward each other in down dog, or yanking them as far from your ears as possible, you’re interrupting this organic coordinated rhythm. Can you tap into your innate harmony of movement?

(NB: The wings in part 2 aren’t perfectly timed. My body reading skills are keener than my video editing skills. You get the idea, though: the scapulae get a move on pretty early in the arm arc.)

What do the lats do?

The lats extend, internally rotate, and adduct the arm. Try this with a block. It's a lot harder than it looks!

Anantasana challenges and tips

This is one of the most challenging yoga poses for me. It requires balancing on a bony knob at the top of the thigh called the greater trochanter. That landmark is shown here on the skeleton and in vivo on me. You can see that this is the widest cross section of my lower body (true for many women), so in this asana I’m perched on a wobbly outcropping. Plus, I don’t have much extra cushioning to fill in the contours and help with equilibrium. Plus plus, I have wide metatarsals and narrow heels. It’s hard to see in this asana photo, but only a sliver of my forefoot is contacting the floor. Structural variation in bone shape and body morphology do make certain poses more or less accessible!

Here’s a tip that serves me well in anantasana: press your foot strongly into the floor. That activates the musculature in the region of the greater trochanter and so pads the bone in a broader, more stable base of flesh.

Foundation position in 3-legged down dog

If you’ve ever taken a class in which I’ve taught 3-legged down dog, you’ve heard these entry cues: “Step your feet a little closer to each other. Lift your right leg hip height.” Centralizing the standing leg (green line) makes it easier for your hip muscles to keep your pelvis level when it’s supported by only one limb. We can change the demand placed on those muscles by shifting the foundation position. What if we start with the feet mat-width apart (yellow lines)? In that case, the base of support is farther from the weight it holds. Harder, right? How about entering from crisscrossed feet? In that case, the supporting muscles are in a longer state and muscles are disadvantaged outside of midrange. Vary the load demand on your hip muscles simply by altering foot placement.

Screw home mechanism

The term “screw home mechanism” refers to the nifty process by which your knee garners added stability when you move from a bent to a straight leg. As you straighten your leg, the tibia (the larger of the two shin bones) laterally rotates (turns toward the pinky toe side of your foot) relative to the femur (thigh bone). That “locks” the knee joint into place by tensioning the cruciate ligaments. This is different from the “locking out” i.e., hyperextension, of the knee that perennially gets a bad rap in yoga classrooms. These inner workings of the knee joint are depicted externally in the video: when my leg is bent, the green line on my thigh tracks with the purple dot at the top of my shin bone. As I step up onto the block, my shin rolls out and my thigh turns in. Watch the green line glide toward the midline relative to the purple dot.

So let’s give this some asana application: Take the transition into half moon pose. Often we’re wobbly when the standing knee is bent and recapture some equilibrium after drawing the leg straight. Temporarily, anyhow. Could that recovery be related to the added stability of the knee when it straightens? This also explains why people who’ve previously torn the ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) sometimes experience discomfort in vira 3: the screw home mechanism tautens the cruciate ligaments and in vira 3 that tension happens under a ton of load. Bending the knee slightly usually affords relief. Then consider the transition from vira 2 into triangle pose: pressure rolls to the outer foot in part because the screw home mechanism transfers weight to the lateral arch of the foot (an important element in walking, since that’s the weight-bearing arch). Now external hip rotation in this pose becomes extra important. Screw home turns the lower leg laterally; without sufficient effort toward turning the thigh in the same direction, you get a torqued knee.

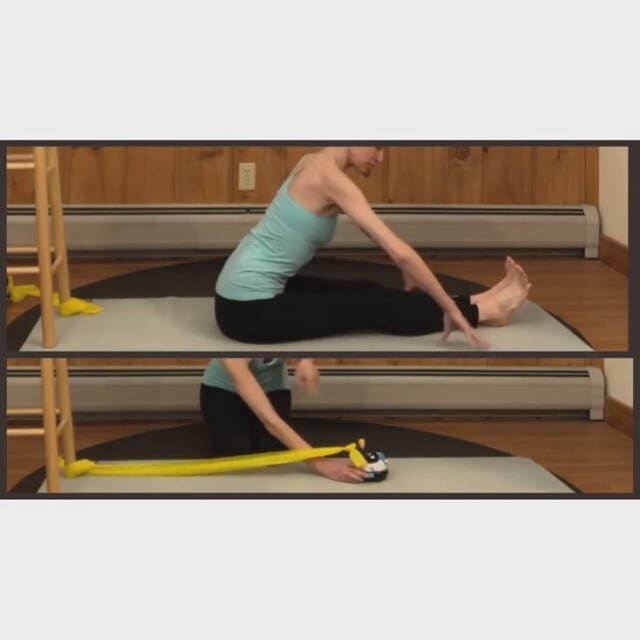

Why use blankets in seated hamstring stretches?

Why does sitting on blankets help people whose hamstrings resist seated forward bends? Here’s a quickie video explanation.

Never let your knees go past your toes!

What's the anatomical reason why yoga teachers cue weight in the heels in bent-legged poses, like utkatasana? Watch this video, then read on for the difference between holding a yoga shape and real life.

OK, so I’m not supposed to let my knees glide forward of my toes in yoga, but I adopt that very leg configuration each time I walk downstairs. What’s the difference? Time. You don’t pause for a 5- to 10-breath hold on each step. Time increases load on tissues. Now, your tissues may well be—and likely are—sufficiently robust to support you in utkatasana with your knees racing far ahead of your ankles, so neither the sky nor your lower extremity is likely to fall if you assume that “misalignment” in this asana. But some students do report knee discomfort when they transfer weight to the balls of their feet (try it momentarily and see!) so I tend to toe the party line on this cue. But sans catastrophic predictions about impending damage. If you can handle a flight of stairs, there’s little chance a yoga pose will send you to the ER.

Shoulder or wrist discomfort in urdhva dhanurasana?

Compare these two urdhva dhanurasana variations. Placing blocks under the hands alleviates wrist discomfort in this pose. Elevating the hands on blocks shifts some weight out of the hands and into the legs. It also creates more space in the shoulders, so a less extreme angle is demanded of the wrists.

Headstand assessment

In headstand, gravity’s plumb line should drop through the cervical spine (AKA neck). That way the neck’s natural curvature can help to distribute the weight of the rest of the body. The left-hand photo illustrates this arrangement. If the upper back rounds, as shown in the right-hand photo, gravity’s plumb line shifts over the ponytail. The cervical vertebrae then translate forward (like jutting your head to see a computer screen) and the weight-distributing curvature disappears. Dolphin pose can be used as an assessment to determine whether a student has sufficient shoulder opening or organization to approach headstand.

Organizing the shoulder blades in shoulder stand

How do you get your cervical spine (your neck) off the floor in shoulder stand? By organizing your shoulder blades. In shoulder stand your shoulder blades retract (move toward your spine) and downwardly rotate. Visualize the shoulder blade as a peninsula, like Florida. The bottom tip, called the inferior angle, is Miami. The Florida panhandle is the spine of the scapula. In shoulder stand, the panhandle creates a shelf on which you can perch your body weight. But if you depress your scapulae (yank them away from your ears) as you enter the pose, you position the panhandle too low to serve as a shelf and you’ll feel the vertebrae at the bottom of your neck press into the floor.

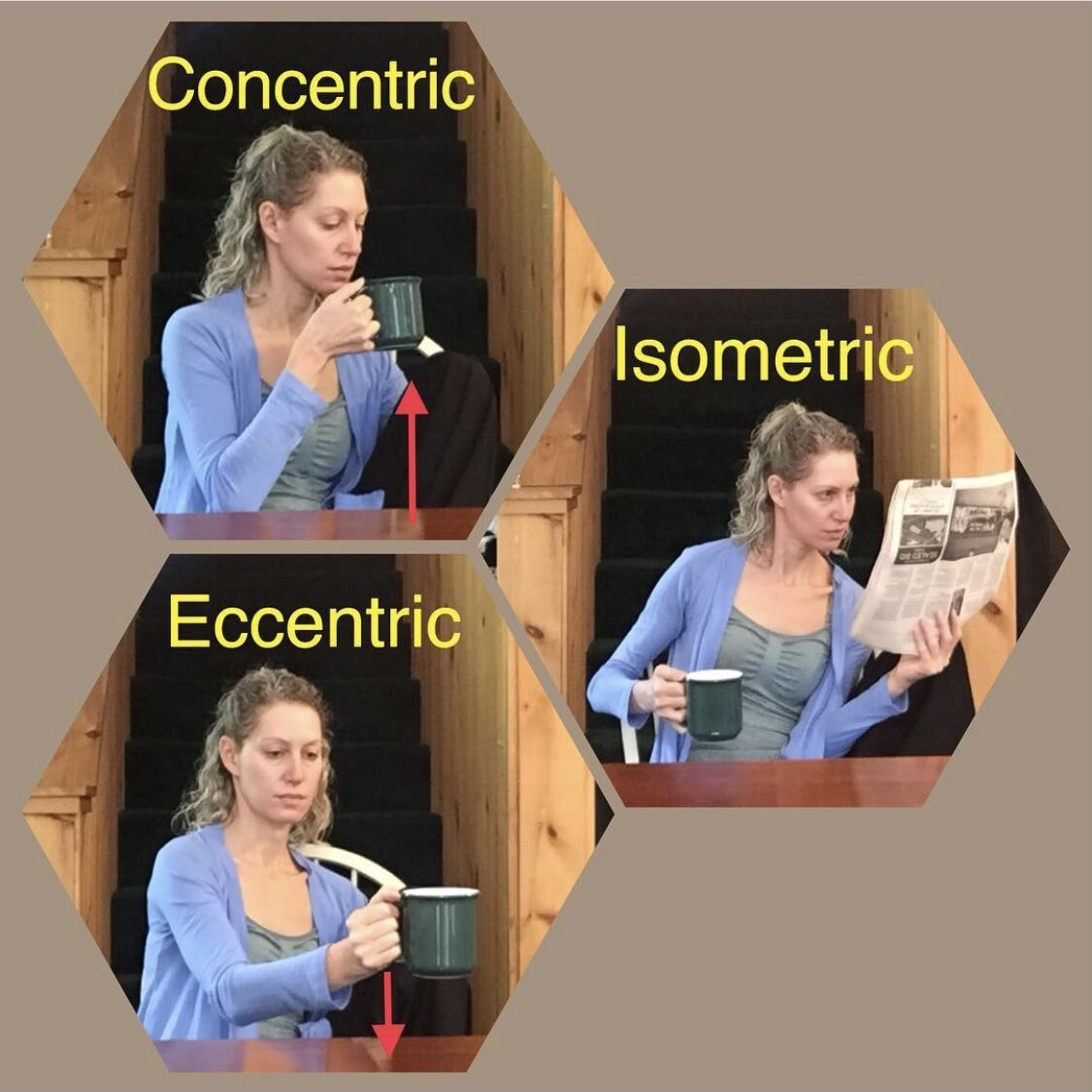

Types of muscle contraction

On concentric contraction, muscle fibers shorten. For example, when you carry a coffee cup to your lips (elbow flexion), your biceps shorten. On eccentric contraction, muscle fibers elongate WHILE STILL CONTRACTING. For example, your biceps get longer when you put the cup down on the table, but they’re still contracting to slow down the movement—otherwise hot coffee would splash on your wrist when the mug bangs down on the hard surface. When no length change happens, that’s an isometric contraction. Like if you find this gallery entry so darn thrilling that your coffee cup is hovering in midair while you read.

Muscle Contraction Type Tutorial

What the heck is an eccentric, concentric, or isometric muscle contraction? If you're baffled by this terminology, I made a tutorial for you!

Three ways your quadriceps can contract

Concentrically: Going upstairs your vastii shorten to hoist your weight up onto the next step. ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Eccentrically: Going downstairs your vastii lengthen WHILE STILL CONTRACTING to slow your descent against the pull of gravity.

Isometrically: Imagine a public restroom. You assume your hovering squat. From there, your quads contract without changing length in order to hold your derrière poised above the can—so you don’t have to hold “it.”

Is hyperextension dangerous?

Stop me if you’ve heard this pearl… No, hyperextending does not wear away the cartilage in your knee. If it did, we hyperextenders would do major damage simply by waiting for the bus, standing in line at the supermarket, propping our feet up on a desk… Thank goodness, your body is way more robust.

Some knees can hyperextend. Some can’t. Allowing your body to do something it’s able to do won’t break you. Okay… Are there reasons to avoid hyperextension? Yes. Read on.

Reason 1: Hyperextension hurts your knee. If this is you, do learn how to avoid hyperextension. (Which muscles will you use to do this? See below.)

Reason 2: Hyperextension in poses like triangle hurts your ankle. Some hyperextenders feel an unpleasant compression in the back of the ankle because knee hyperextension increases ankle plantarflexion. If this is you, learn how to control your hyperextension. (See the next gallery post for more on the connection between knee hyperextension and ankle compression. )

Reason 3: Yoga privileges extreme-range joint flexibility. We can balance that by building the strength and body-awareness to muscularly hold a joint in a chosen position, rather than simply slumping into gravity. Learning how not to hyperextend (engage your hamstrings and gastrocnemius) is a valuable stability and proprioceptive exercise.

Bottom line: you won’t erode your meniscus by hyperextending. Nor will you “overstretch” the back of the joint capsule. (For more info on this, scroll two entries down to the gummy worm post.) There are benefits to be gained from backing off hyperextension—just not the ones that receive catastrophizing fear-mongering diffusion.

Is hyperextending your knee in trikonasana dangerous?

Well… Does it hurt? If it hurts, press your calf toward your shin to come out of the hyperextension. If it doesn’t hurt, maybe it’s just something your knee is capable of doing. Knee extension is stopped by tissue tension at the back of the joint capsule. Some of us have more laxity there, some less. “But won’t I overstretch the tissues at the back of the knee?” Whether or not we can “overstretch” (or even stretch!) these tissues, especially in a low-load scenario like a yoga pose, is up for debate. I don’t have a definitive answer on that one. I also don’t hear a ton of knee complaints from hyperextenders in this pose; they more frequently report...

...ankle discomfort. Take a look at the back of my ankle in the blow-up. See how white and wrinkly it looks? Knee hyperextension moves my ankle into greater plantar flexion, and that often registers as compression at the back of the ankle. There may well be benefits to resisting hyperextension...but perhaps not for the reasons commonly touted. (Though, again, if hyperextending your knee in this pose hurts, that’s a great reason not to do it!)

Can you "overstretch" ligament?

Can you “overstretch” your ligaments in yoga? Ligament (along with many other body tissues) has properties similar to this gummy worm. When I stretch the gummy and then let go, the candy remains elongated, as in the “before” photo. If I walk away and come back some time later (it does take a bit), I’ll find the worm has shrunk back to its original length, as in the “after” image. Go ahead and enjoy a long juicy stretch. Your tissues will return to their resting length.

But you CAN injure ligament, right? Oh yes. Anyone who’s ever sprained an ankle can attest to this. But sprains usually occur as a result of a quick, sharp trauma; not a slow steady stretch. So what are the yoga implications here? Remember that the worm, and your tissues, need time to return to resting length. So maybe it’s not a great idea to heave a heavy suitcase down steep stairs while wearing high heels immediately following a yin workshop. But a long hold in upavistha konasana won’t break you.

Pelvic movement ➡️ spinal movement

Your spine sits on your pelvis, like an artwork perched atop a pedestal. Any movement of the base will ripple up the chain. When you tip your pelvis forward (anterior tilt), your spine backbends, or extends. When you tuck your pelvis (posterior tilt), your spine rounds, or flexes. When you lift one hip (elevation), your spine C curves, or laterally flexes. When you rotate your pelvis, the spine twists.

This is your neck. This is your neck in a slump. Any questions?

OK, further explanation is warranted. First, you have 7 bones in your neck, but I have only 5 blocks, so please forgive the inexact representation.

The left-hand photo represents the natural curve of your neck. When you slump, the bones in your neck translate forward, as shown in the image on the right. That juts the weight of your head forward of your torso, demanding a great deal of work from your posterior neck muscles to hold your head up and potentially leading to neck and shoulder complaints. Hence the common cue to lift the chest. BUT...

If you lift your chest too much you flatten the natural curve of your thoracic spine, your upper back. So, yes, unslump by lifting your chest, but can you simultaneously feel your breath plumping up your upper back?

Going Along for the Ride

I found this car among my niece and nephew’s toys. Aha, what a great way to illustrate how the spine “goes along for the ride” in forward bends!

The car advances and the passenger is carried along. Just so, as you enter a forward bend, your pelvis tips forward and the spine just goes along for the ride. In the first phase of a forward bend, the aim is to avoid rounding the spine. (It’ll round the very end, if you’re sufficiently flexible). If the hamstrings stop your pelvis from tilting, your spine slumps to bring your head closer to your legs. In the bottom video, the yellow band (hamstrings) tautens, stops the car (pelvis) from progressing, and the guy (spine) keeps going.

Is rounding your spine in a forward bend risky? Honestly, unless there’s a preexisting condition, probably not. You’re unlikely to load your back sufficiently here to create an injury. But the more you focus on rotating the pelvis over the thighs, the more you stretch your hamstrings (if that’s your goal) and the more you build awareness of how various body parts participate in the movement.

Stability and Mobility Are Not Opposites

How am I able to keep my balance while standing on a squishy surface and moving somewhat quickly through space? Feet are mobile. Each foot has 26 bones. That means a lot of moving joints. The muscles in my lower leg constantly and minutely wriggle those joints to enable me to maintain equilibrium. Balance is not static, it’s a dance.

We often see mobility pitted against stability: if a body part is mobile it must be unstable and if it’s solid it must be rigid. Here we see that stability (not falling on my tuchus) is a product of finessed mobility.

Spice up your bridge pose.

Let’s talk lever length. The farther I walk my feet from my hips, the longer the lever and the more effort I demand from my hip extensor muscles. It’s a devilishly effective way to progress the difficulty of a familiar bridge pose.

Why might we want to make bridge more challenging in this particular way? Well, yoga does a lot to stretch the backs of the legs. It’s less effective at strengthening that area. Building posterior chain strength seems to be really useful in countering common yoga hamstring attachment and SI complaints. The evidence for that claim is purely anecdotal—I’m speaking from my personal experience and referencing conversations I’ve had with many, many friends in the yoga world. But targeting your hamstrings and glutes is also helpful for a wide variety of non-yoga activities: bike riding, hiking uphill (or climbing stairs), squatting over a dirty public toilet seat…

What is a tendon?

Ye olde Twizzler analogy shows the relationship between muscle, fascia, and tendon.

Muscles Move Bones by PULLING

Imagine that the lines on my leg are strings. Which string would you pull to straighten my knee, pink or blue? Which would you pull to bend my knee?

This demonstration illustrates how muscles move the body: they PULL one bone toward another. Understanding this principle is key for movement teachers who need to determine which muscles/muscle groups create a particular movement. (And for clarity’s sake: your thigh muscles aren’t skinny strings. The marker just shows the line of pull.)

Ready for the answer key? Pink = straighten; blue = bend.

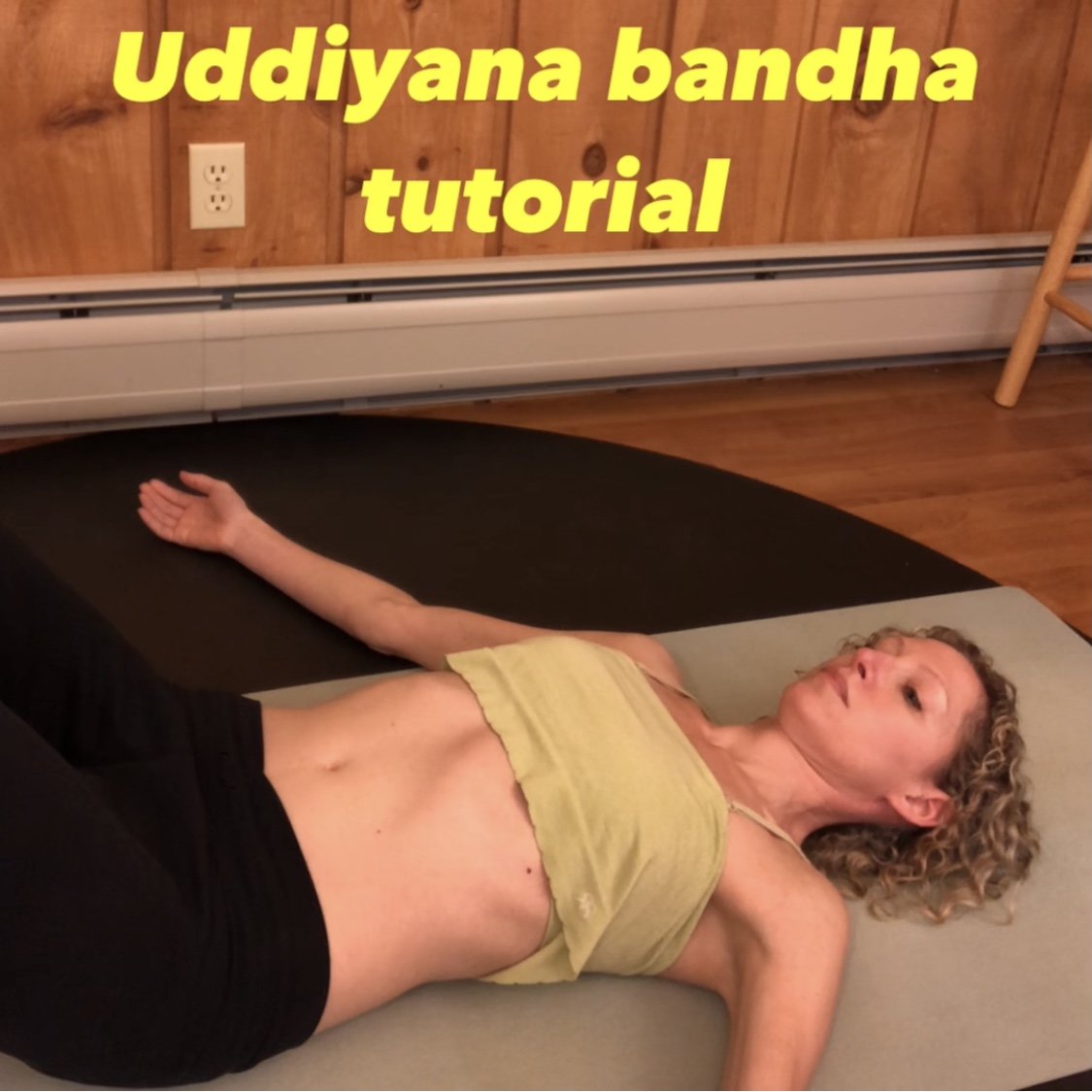

Uddiyana Bandha Tutorial

Heads up: this is gonna get geeky.

Place your hands on your ribs. Take a deep inhale. Feel them expand? OK, now exhale. Flare your ribs again BUT DON’T ALLOW AIR TO ENTER. If you didn’t tuck your chin into your neck (jalandhara bandha), you probably felt an uncomfortable catch in your throat. That’s because expanding your ribs increased the volume of your thoracic cavity, creating a low-pressure chamber. (See footnote at bottom.) Normally, this is how you initiate an inhalation: because the pressure in your chest is lower than the air pressure outside your body, air floods to the low-pressure area. If you didn’t tuck your chin, you felt the inside of your throat get tugged down instead of air. Ick. Because the chin lock doesn’t allow air to enter, you essentially have a vacuum in your thorax. And we all know that nature abhors a vacuum. So that vacuum needs to be filled. You’ve prevented air from entering your chest from the top, so your abdominal organs will instead get sucked up into your rib space. That’s why you see my belly hollow in the video and that’s the “flying upward” that gives uddiyana bandha its name.

(Your diaphragm also flies upward. We could get into the diaphragm’s role in all this, but I think this is enough anatomical dorkiness for one post.)

(And here’s the footnote: Volume and pressure are inversely proportional. Greater volume = lower pressure. Imagine you’re packing a suitcase. Your wardrobe will be more smooshed in a smaller bag and less pressed together in a larger one, right?)

What lower leg muscles do you use to balance?

Here’s the deal: balance is not stillness. Balance is constant adjustment. (#lifelessons) One of the muscles that organizes your ankle when you stand on one leg is tibialis anterior. It lifts the inner arch of your foot. (It also flexes your ankle, as illustrated here.) The peroneals, which run down your outer shin, lift your outer arch. These antagonist muscles finesse your ankle (aka, make it wobble) to prevent you from falling over in a balancing pose, like ardha chandrasana, half moon, or vrksasana, tree pose.

Balance is essentially micromanaged wobbling.